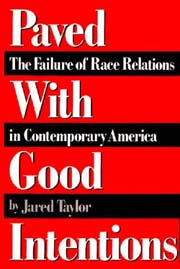

2004 edition by New Century Books, 421 pp., indexed, $15.95 (soft cover)

This is the book that established Jared Taylor as an expert and commentator on race relations. The publishers of American Renaissance have reprinted this classic with a new preface for the 2004 edition by Jared Taylor.

Race is the great American dilemma. This has always been so, and is likely to remain so. Race has marred our past and clouds our future. It is a particularly agonizing and even shameful dilemma because, in so many other ways, the United States has been a blessing to its people and a model for the world.

The very discovery by Europeans of a continent inhabited by Indians was an enormous crisis in race relations — a crisis that led to catastrophe and dispossession for the Indians. The arrival of the first black slaves to Virginia in 1619 set in motion a series of crises that persist to the present. Indirectly, it brought about the bloodiest war America has ever fought, Reconstruction, segregation, the civil rights movement, and the seemingly intractable problems of today’s underclass.

Despite enormous effort, especially in the latter half of this century, those two ancient crises remain unresolved. Neither Indians nor blacks are full participants in America; in many ways they lead lives that lie apart from the mainstream.

After 1965, the United States began to add two more racial groups to the uneasy mix that, in the heady days of civil rights successes, seemed finally on the road to harmony. In that year, Congress passed a new immigration law that cut the flow of immigrants from Europe and dramatically increased the flow from Latin America and Asia. Now 90 percent of all legal immigrants are nonwhite, and Asians and Hispanics have joined the American mix in large numbers. The United States has embarked on a policy of multiracial nation-building that is without precedent in the history of the world.

Race is therefore a prominent fact of national life, and if our immigration policies remain unchanged, it will become an increasingly central fact. Race, in ever more complex combinations, will continue to be the great American dilemma.

Nevertheless, even as the nation becomes a mix of many races, the quintessential racial divide in America — the subject of this book — is between black and white. Blacks have been present in large numbers and have played an important part in American history ever since the nation began. Unlike recent immigrants, who are concentrated in Florida, California, New York, and the Southwest, blacks live in almost all parts of the country. Many of our major cities are now largely populated and even governed by blacks. Finally, for a host of reasons, black/white frictions are more obtrusive and damaging than any other racial cleavage in America.

In our multiracial society, race lurks just below the surface of much that is not explicitly racial. Newspaper stories about other things — housing patterns, local elections, crime, antipoverty programs, law-school admissions, mortgage lending, employment rates — are also, sometimes only by implication, about race. When race is not in the foreground of American life, it does not usually take much searching to find it in the background.

From the Preface to the 2004 Edition:

Why read a book that first appeared in 1992? I believe there are two reasons. First, it is still an eye-opening account of a series of terrible mistakes we have made with regard to one of the most sensitive and difficult aspects of our nation’s history. Some of the characters in America’s continuing racial drama have changed since 1992, but a surprising number have not, and the empty sloganeering that passes for public discourse has slackened only a little. As we will see, I made a number of compromises in order to have this book published, but the compromises lie mainly in what I did not write. I think most of what I did write stands up well more than a decade later. Many readers of this book have told me it angered them, enlightened them, and in some cases shifted their thinking substantially. I would like to think it still has that power — but I am the book’s author. Readers will judge for themselves.

The second reason to read this book is less important but of a certain historical interest. In its own modest way, I believe Paved With Good Intentions was part of a steady evolution in what it is permitted to say about race in the American mainstream.

When it appeared in 1992, the obligatory mainstream

view was that white racism

causes black failure. If blacks are poor, commit crimes, have children out of wedlock, drop out of school, or take drugs, it is due to the accumulated oppression of slavery, lynching, segregation, and institutional racism.

I wrote this book to refute this view, to show that American society as a whole does not oppress blacks and that, indeed, it often offers them race-based benefits of the kind that go under the name of affirmative action.

From the Reviews:

The most important book to be published on the subject in many years.

Peter Brimelow, National Review (read the full review)

A vitally important, shattering book.

Samuel Francis, Washington Times

Easily the most comprehensive indictment of the race-conscious civil rights policies of the past three decades.

Clint Bolick, The Wall Street Journal

This is a painful book to read, yet hard to put down.

The conspiracy of silence is part of Mr. Taylor’s tale as well, which in part explains why its impact is so unexpected and so profound. Let us hope that this important book does not become another victim of the conspiracy of silence and that it gains the visibility and attention it deserves.

Richard Herrnstein, Harvard University

Meticulously researched and powerfully argued, Paved With Good Intentions shows just how specious and hypocritical is the conventional wisdom on America’s race problem. As Mr. Taylor demonstrates, whites and blacks have deluded themselves into believing that black failure is invariably the result of white racism.

Robert R. Detlefsen, Hollins College

The most outspoken book the Club has ever offered. And the most painful.

Conservative Book Club

The most scurrilous work about American blacks since Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman was published in 1905.

Baltimore Sun